THE MAIN GATES to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Delhi are next to the metro station on Aurobindo Marg, a busy artery that runs through the south of the city. When I arrive on this occasion, it is a late March morning; the air is warm but not yet vibrating with the full heat of summer. The young man who sells flower-patterned plastic wallets to protect medical histories is standing in his usual place just outside the gates. I pass him and turn left at the tree that provides shade for a few of the thousands of people who spend hours at AIIMS waiting—for consultations, for tests, for results, for information about where to go next. A road skirts the edge of the campus, a cordon separating pedestrians from a huddle of stationary green and yellow auto-rickshaws and the passing traffic. When a gap appears between vehicles, I step over the fraying red rope and cross to the concourse that extends out from the main outpatient building. Small clusters of people sit on the floor, many on sheets made from recycled plastic packaging, bright with primary colors. As the sun gets stronger, people squeeze more tightly into the segments of shade cast by roof and walls. Sometimes patients are obvious—identifiable by dressings on a wound or a drainage bag on the floor beside a frail body—but not always. The inability to distinguish patients at first sight makes visible the fact of shared affliction—how illness and treatment seeking extend beyond the skin of an individual to encompass a network of surrounding people.

Opposite, outside a waiting hall under construction, some women have laid rinsed-out clothes over a railing to dry. I watch as a security guard shouts at them and gestures aggressively with his lathi, a wooden baton, toward the clothes. The women reluctantly pull the garments from the railing. (When I walked back through a few hours later, different clothes hung in their place.) The queue outside the pediatric outpatient department on my left has already subsided—those who didn’t reach the front before the appointments ran out will try again tomorrow. Outside the generic drugs pharmacy the queue will disperse only when the shutters are lowered in the late afternoon.

Medical students are rarely noticeable around this area of AIIMS, but it is with and through these throngs of patients, an average of 10,000 passing through each day, that India’s most esteemed young doctors are formed.

Turning right, I enter the institution’s administrative and educational nerve center. This is the boundary between the clinical and the academic worlds of AIIMS—between the hospital and the college. The sudden absence of patients and families is striking; they are not permitted to congregate here. If they drift off course during the effort to navigate the hospital labyrinth, they will be policed away from this haven—a large quadrangle laid with a well-irrigated jade-green lawn, edged with palm trees and rose beds, and stone curbs painted in warning stripes to discourage sitting. The huddle of buildings seems to cushion sound, which adds to the qualitative difference between the two environments. It is calm here, amid students and faculty milling among the hostels, library, offices, and consultation rooms. This is a different place, where precarity is hidden.

I skirt the quadrangle and cross the road, passing into the heart of student life. The men’s hostels stand on one side of the tree-lined road (the women’s hostels are pointedly situated on the opposite side of the campus). On the other side are the photocopying and stationery shop, general store, and outdoor café. Students are suddenly everywhere, chatting in groups or walking purposively toward the hospital in their white, or graying, coats with stethoscopes slung around their necks. These, we are informed by the media and the medical establishment, are examples of India’s “best”—its most gifted, dedicated, promising medical students. And there are moments, even when I am in the thick of uncovering the many caveats and complications that this description disguises, that I find myself looking at these young people as though they really are different—special—somehow.

It was 2016 and I had returned to AIIMS to visit two students, Purush and Sushil. I first met them during the final year of their MBBS degree; their experiences, among others, inform this book. Now they were studying for the fiercely competitive postgraduate entrance exams that would determine the type of medicine they would specialize in. We discussed their preferred courses and colleges. Sushil acknowledged that studying somewhere else might lend him a broader perspective. Then he paused and looked at me. “But AIIMS is AIIMS,” he said with a grin. Simply put, what follows is an attempt to understand what this exceptionalism means: for students at AIIMS, for the doctors they might become and the patients they might treat, and for the deeply inequitable landscape beyond the institution’s gates.

The All India Institute of Medical Sciences opened its gates in 1956, but as I describe in chapter 2, the seeds for the institution were planted while India was still a British colony. Modeled on the prestigious Johns Hopkins University in the United States, AIIMS embodied the primacy of science and technology in independent India’s developmental project. It was intended to set a new standard in Indian biomedical research and practice while also training new generations to remedy the ills of a vast and impoverished emergent nation.1 Today, AIIMS is an enormous and ever-expanding government-funded teaching hospital. It is anomalous in India’s public healthcare landscape for employing many of the country’s most respected doctors, who provide a high standard of care at nominal cost to predominantly poor and marginalized patients who often travel long distances in search of help.

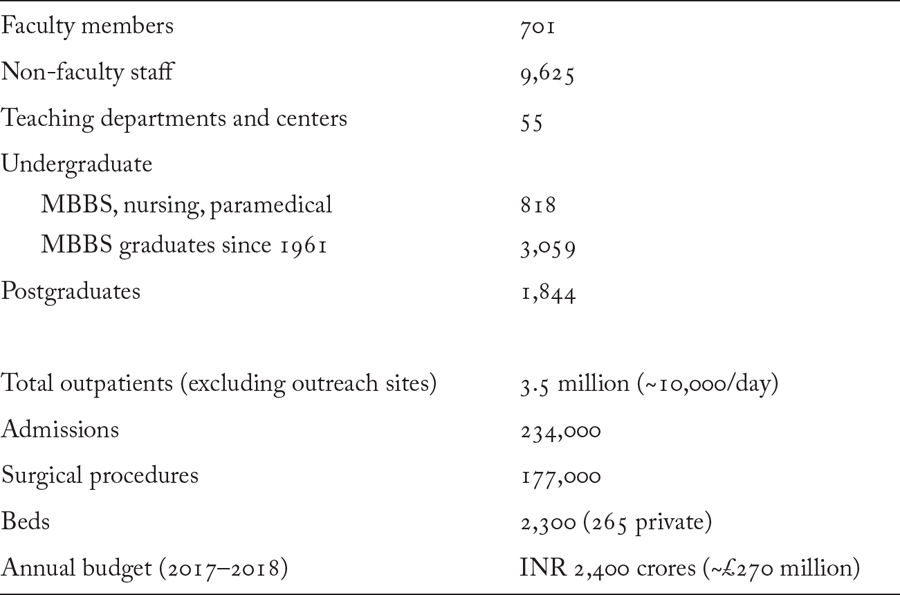

The AIIMS Act of 1956 declares AIIMS an institution of national importance. Its three founding objectives are to set national standards in undergraduate and postgraduate education, to establish the highest standard of facilities for training in “all important branches of health activity,” and to achieve self-sufficiency in postgraduate education2—while providing care to some of the country’s most underprivileged patients. This complex mandate makes for a formidable and unrelenting challenge. Figure 1 captures the scale for which the institution is famous and hints at the pressure under which it operates.3

People acquainted with healthcare in India often have an opinion about AIIMS, especially in northern India, and even more so if they have lived in Delhi. It is a phenomenon as much as a concrete landmark. It is not uncommon to know someone who has been treated at AIIMS or, within a particular milieu, to know someone who knows someone whose relative is or was an AIIMS doctor. But impressions also form during years of passing within sight of the modernist complex, whose neon sign alerts the city to its presence. Or while stuck in traffic outside the hospital gates, where patients and families sleep on the pavement for want of anywhere else. Or through the media, which fuels public perceptions of the institution, for better and worse,4 and which these days brings news of the next generation of All India Institutes being established around the country.5 Even if AIIMS means little to an individual, from many locations in Delhi it is possible to reorient oneself via the ubiquitous road signs pointing the way to the institute. AIIMS is there: embedded in the landscape of Delhi, and in imaginations both within and beyond the city.

Ethnographic studies of medical institutions in the Global South, while still relatively few, often share a concern with the ways in which resource scarcity reveals the instabilities and contingencies of biomedicine in different terrains, demanding improvisation on the part of both medical professionals and patients in order to achieve some form of therapeutic outcome in straitened circumstances.6 Patients and doctors at AIIMS, meanwhile, suffer more from limited time and space than from an explicit lack of institutional resources, pressured though these are. If anything, the pressure on resources at AIIMS illuminates how profoundly they are lacking beyond its gates, as patients crowd into the OPD to seek the care they cannot access elsewhere.7 AIIMS is not, however, an aesthetically therapeutic environment for either patients or doctors. It is crowded, confusing, uncomfortable, not always clean. It sometimes suggests less an effort to impart health than a perpetual scramble to stave off decay.8

A dedicated government budget does ensure that AIIMS is equipped, staffed, and maintained to an unusually high standard for an Indian public healthcare facility. In principle, the 1956 AIIMS Act also guarantees the independence and autonomy of the institute. In practice, however, AIIMS has always been a political institution that has periodically suffered from and sometimes colluded with direct interference in its functioning. The central government minister of health and family welfare is also president and chairman of AIIMS, and members of Parliament and civil servants account for half of the 18-member institute body and just under half of the governing body.9 The directorship of AIIMS is known to be a political appointment, and several senior faculty members wryly informed me that they would never be considered for the position because they were not on sufficiently good terms with the powers that be. A retired faculty member told me that political interference became routine only in the 1980s, when AIIMS became the hospital of choice for politicians, following the fatal shooting of Indira Gandhi in 1984.10 However, T. N. Madan cites an informant telling him in the 1970s that “the long arm of the government is very visible in the manner in which the institute is run.”11 In the last few years, wrangling over the locations of new branches of AIIMS has reemphasized their political nature.

“Corruption talk” is ubiquitous at, and in relation to, AIIMS. It ranges from the jaan-pechaan, or personal connection, that some patients utilize to access treatment, to allegations of kickbacks from off-campus pathology laboratories, caste-based discrimination toward students and faculty, and allegations of systemic malpractice. In the chapters that follow, I don’t attempt to analyze corruption as a distinct entity, or to interrogate the truth or falsity of allegations—rather, where corruption talk arises, I approach it as an illustration of how AIIMS reflects the values and practices of the broader society in which it is embedded.12

Officially AIIMS is a tertiary institution, and the lack of a tiered public healthcare system in India means that AIIMS actually exists as an independent entity, as illustrated by the vast number of self-referrals to the hospital. For the majority of patients without privileged access to individual doctors who are directed to the hospital, to be “referred” to AIIMS does not involve internal communication within a healthcare system as the term might imply. Rather, it is to be “sent”—the Hindi bhej dena more accurately reflects the experience of being told to seek further treatment at AIIMS by a doctor who has reached the limit of ability or inclination to treat a complex and/or chronic condition.13 Some patients are directed to seek an appointment at a particular department, with no guidance about how to navigate the appointment system or the overwhelming hospital campus itself. Others are simply instructed to “go to AIIMS,” feeding an impression of the institution as an almost mythical site of last resort. On arrival, the pursuit of treatment often reverts to square one.

This fragmented system has complex consequences for both patients and doctors at AIIMS, as I illustrate in chapters 5 and 6. It also influences the impressions made upon students at an institution that, as well as being a famous public hospital, occupies a seemingly unassailable position atop the hierarchy of Indian medical education.

In recent years, the position of AIIMS as the country’s most prestigious medical college has been formalized by the promotion of an annual ranking of colleges by the news magazine India Today. During my research, a framed cover of the magazine declared this continued domination from a wall in the office of the institute’s academic dean. AIIMS is also the only Indian medical college in the Centre for World University Rankings’ top 1,000 degree-granting institutions. In 2018, India’s Ministry of Human Resource Development added a new medical college category to its own National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF). In a group of 25 colleges, AIIMS New Delhi occupied the top spot by a significant margin, set apart even from its fellow institutions in the top five: Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, Christian Medical College in Vellore, Kasturba Medical College in Manipal, and King George’s Medical University in Lucknow. As with all exercises, the metrics used by the NIRF invite scrutiny and are open to interpretation.14 What is most interesting for the purposes of this book, however, is the inclusion in the NIRF of a “perception” score, which combines survey data from employers and research funders, academic peers, and the general public about their perceptions of the colleges, together with the number of postgraduate students admitted from “top institutions” each year. AIIMS is unique in the medical college category for having a perception score of 100. What does it mean for a single medical college to be considered so unequivocally “the best”—for the doctors it trains and for the society in which they will practice?

1. The Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), India’s most prestigious engineering colleges, were established at the same moment with a mandate to integrate the highest standards of science and engineering into the development of the newly independent nation. There are many parallels between the IITs and AIIMS, their place in the national imagination, and the manner in which they reproduce social hierarchies, as I discuss throughout this book. In doing so, I draw on Ajantha Subramanian’s work on IIT Madras, The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

2. Government of India, “The All India Institute of Medical Sciences Act, 1956” (1956), 5–6, https://www.aiims.edu/images/pdf/aiimsact.pdf.

3. As an indication of the institution’s growth, in his study of AIIMS in the 1970s, T. N. Madan cites the following figures for 1974–1975: 450,291 outpatients, 19,782 admissions, and 33,949 surgical procedures. T. N. Madan, ed., Doctors and Society: Three Asian Case Studies: India, Malaysia, Sri Lanka (Ghaziabad: Vikas, 1980), 45. In 2016, a long-planned expansion was sanctioned, which includes the creation of an additional 1,800 beds across seven departments on a new 15-acre site. Press Information Bureau, Government of India, “Health Minister gives go ahead for the expansion of AIIMS Trauma Centre,” February 22, 2016, http://www.aiims.edu/images/press-release/HFW-AIIMS%20Trauma%20Centre-22%20Feb2016.pdf.

4. As an illustration of its media profile: a Google search for news stories related to Safdarjung Hospital—an older government institution directly opposite AIIMS—returned 12,700 results while the equivalent search for AIIMS New Delhi produced 468,000 results. News articles and opinion pieces about AIIMS are often critical, alleging corruption (M. Rajshekhar, “High Patient Inflow, Corruption, Nepotism and Talent Exodus: The Problems That Have Plagued AIIMS,” Economic Times, March 12, 2015), dysfunction (D. Gupta, “Tidy up Delhi’s AIIMS before Building Many More across India,” Times of India, July 21, 2014), and neglect or malpractice (V. Unnikrishnan, “AIIMS Director Mishra in Trouble: RS MPs Seek Privilege Motion,” Catch News, August 3, 2016). Stories also emphasize the unparalleled expertise of AIIMS doctors in performing complex surgery on patients with rare conditions: “17 Kg Tumour Removed from Woman’s Abdomen,” India Today, March 4, 2015; N. Chandra, “Eight Hours, 30 Doctors and a New Lease of Life: Conjoined Twins with Fused Chest, Abdomen Separated Successfully at AIIMS,” India Today, July 22, 2013, 10. During the violence in the Kashmir Valley in the summer of 2016, a team of AIIMS eye surgeons flew to the state to examine victims of the pellet guns used by the army to subdue protesting citizens, several of whom were airlifted to AIIMS for surgery (N. Iqbal, “Kashmir Pellet Gun Victims Pin Their Hopes on Doctors at AIIMS,” Indian Express, July 27, 2016). Young victims of horrific crimes in and around Delhi, most notably child rape, are also usually taken to AIIMS (D. Pandey, “Child Rape Victim Shifted to AIIMS as Outrage Spreads,” The Hindu, April 20, 2013).

5. At the time of writing there were 14 All India Institutes in addition to the New Delhi original, with another 8 on the drawing board. The shortcomings of several of the new institutes are regularly highlighted in the media, including recruitment challenges and inadequate infrastructure. AIIMS New Delhi remains in a class of its own. Although some faculty have been involved in supporting the development of the other institutes, a general disquiet persists about their impact on “brand AIIMS.” Aside from occasional references, this book focuses on AIIMS New Delhi, which I refer to simply as AIIMS.

6. J. Livingston, Improvising Medicine: An African Oncology Ward in an Emerging Cancer Epidemic (Durham NC: Duke University Press: 2012). A. Street, Biomedicine in an Unstable Place: Infrastructure and Personhood in a Papua New Guinean Hospital (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014); C. L. Wendland, A Heart for the Work: Journeys through an African Medical School (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); S. Zaman, Broken Limbs, Broken Lives: Ethnography of a Hospital Ward in Bangladesh (Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis, 2005).

7. V. Patel, R. Parikh, S. Nandraj, P. Balasubramaniam, K. Narayan, V. K. Paul, A. K. S. Kumar, M. Chatterjee, and K. S. Reddy, “Assuring Health Coverage for All in India,” Lancet 386 (2015): 2422–35.

8. Since my research at AIIMS, a hospital modernization program contracted to Tata Consultancy Services has begun to manifest through a new waiting area and updated signage, as well as the early stages of a digital appointment system.

9. In recent years, there have been two particularly visible instances of political interference in the administration of AIIMS. Following the agitation in 2006 against increased quotas of reserved places for students and faculty from Other Backward Classes, which was headquartered at AIIMS with the alleged support of the director (V. Venkatesan, “The Dynamics of Medicos’ Anti-Reservation Protests of 2006,” in Health Providers in India: On the Frontlines of Change, ed. K. Sheikh and A. George [New Delhi: Routledge, 2010]: 142–57), the Congress government’s health minister was accused of persistent interference, culminating in the removal of the AIIMS director (T. Rashid, “Dr. Ramadoss Plays the Boss, Pushes AIIMS Chief to Brink,” Indian Express, June 15, 2006). More recently, the civil servant Sanjiv Chaturvedi was removed from the post of chief vigilance officer at AIIMS following his investigations into 165 cases of alleged corruption over two-and-a-half years—a move widely alleged to have been a politically motivated calculation to protect the interests of senior figures in government and the AIIMS administration implicated by Chaturvedi’s work. Business Standard, “Sanjiv Chaturvedi: The Man Who Uncovered AIIMS Corruption,” 29 July, 2015; N. Sethi, “Parliamentary Standing Committee Report on Corruption in the Hospital Has No Foundation: AIIMS,” Business Standard, June 3, 2016.

10. Several members of the current government have been treated at AIIMS, as were External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and Finance Minister Arun Jaitley before their deaths in 2019. An AIIMS medical board was involved in the investigation into the poisoning of Sunanda Pushkar, wife of MP Shashi Tharoor, which garnered a huge amount of media attention. And in October 2016, a team of specialists from AIIMS flew to Chennai to consult with doctors at the private Apollo Hospital about the treatment of Tamil Nadu Chief Minister J. Jayalaalitha. Following the death of former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee at AIIMS in August 2018, a journalist described him as “a patient AIIMS will remember forever,” given the medical attention he received from the institute’s doctors over several decades. D. N. Jha, “Humble till the End: A Patient AIIMS Will Remember Forever,” Times of India, August 27, 2018. Of course, those politicians admitted to AIIMS are treated in one of its private rooms. Of the 2,300 beds at AIIMS, 265 are private.

11. T. N. Madan, Doctors and Society, 90.

12. D. Haller and C. Shore, eds., Corruption: Anthropological Perspectives (London: Pluto, 2005), 6; S. Nundy, K. Desiraju, and S. Nagral, eds., Healers or Predators? Healthcare Corruption in India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018).

13. V. Das, Affliction: Health, Disease, Poverty (New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, 2015), 159–80.

14. For the NIRF results and an explanation of the parameters used, see National Institutional Ranking Framework, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India, https://www.nirfindia.org/2018/MEDICALRanking.html